Taking a different route and contemplating time out.

Monthly Archives: October 2016

Mole Out Loud #464

Mole Out Loud #463

A quiet day, oddly waiting. And reading the writing of others in preparation for an evening discussion.

Mole Out Loud #462

Mole Out Loud #461

Mole Out Loud #460

Lost

When I was a nipper I discovered I was privy to several personas. I’m not sure when this revelation first came to me, but I think it must have been around the time I found that if I stood on tippaws and stretched right up, I could reach the handle to Mama and Papa’s bedchamber. Just inside the door was a great big looking-glass that rested on the floor, and it was in front of this that I discovered my other selves.

At first I think it was facial expressions I experimented with, then gestures, then voices, all randomly, trying out my muscles. Gradually they became individualised: moles with secrets, moles with limps, moles who were flamboyant, or brave, or big, or tiny, or foreign, old or young or important or pragmatic or dreamy.Sometimes they were not even moles. I would practice the way they stood, held their heads, snorted, squealed, laughed. I would have arguments between these characters, rapidly changing from the one to the other, shrill arguments, reasoned arguments. By this time some of them had names, most were invented but some were inspired by people I had met: Herr Blini bit his nails like the refugee who played chess with Papa, Frau Schmutz had a limp and whistled out of tune like the school cleaner, Mademoiselle Chic smoked cigarillos like the supremely elegant mole who sometimes teetered into the Apothecary; Hans Peter smoothed the pelt of his head like the Lothario who rode his bike without using his paws.

And then there was Maud. I don’t know where she came from. Nor did she. Maud was a foundling. Pinned to her plain shift was a scrap of material, emerald and vermillion, raised velvet. It was all that she had of her Mama’s, nothing else, not even her name. She came to me fully formed, a tiny mole who stood very upright, arms crossed in front of her, ready to take on the world.

By now I no longer needed a looking-glass; these personas were part of me. Or at least they usually were. Somehow the me mole was always there, and although the others were all me as well, I came to realise they came from elsewhere, too. And that sometimes they didn’t. The times they didn’t were when I most needed them.

Like the day I lost my school bag and in it my homework and was too frightened to go back to school. On days like these I was numb; I couldn’t reach my feelers out – not even to Maud.

On the day of the lost homework debacle, when a return to either school or home felt fraught with likely recriminations, I headed for the nether regions of a bookshop in town where a kindred soul in the rather formidable guise of an autocratic dame, guarded the section that held reference works, English language books and esoterica.

Madame von Heldenberg was at her secretaire; beside her a tall glass of steaming dark coffee delivered by an Italian mole who ran the cinema next door. I was too young for coffee but when she saw my distress she sat me down and gave me a golfball sized, black and gold striped humbug from a jar that was refilled every time her son-in-law returned from a trip to England. And once I had my mouth full and couldn’t possibly answer her, she asked me what was the matter.

I had quite calmed down by the time the humbug had reduced enough for me to articulate my words, but what came out was still a jumbled muddle of losing my homework and my personas all at once.

‘Lost’, said Madame von Heldenberg as if that summed up the whole catastrophe. It did. ‘You know, words can take on a personal meaning that has nothing to do with etymology.’ I didn’t know what she was talking about, but she steered me over to the dictionary section. While she went upstairs with some orders, I was to find ‘lost’ in different languages. She gave me

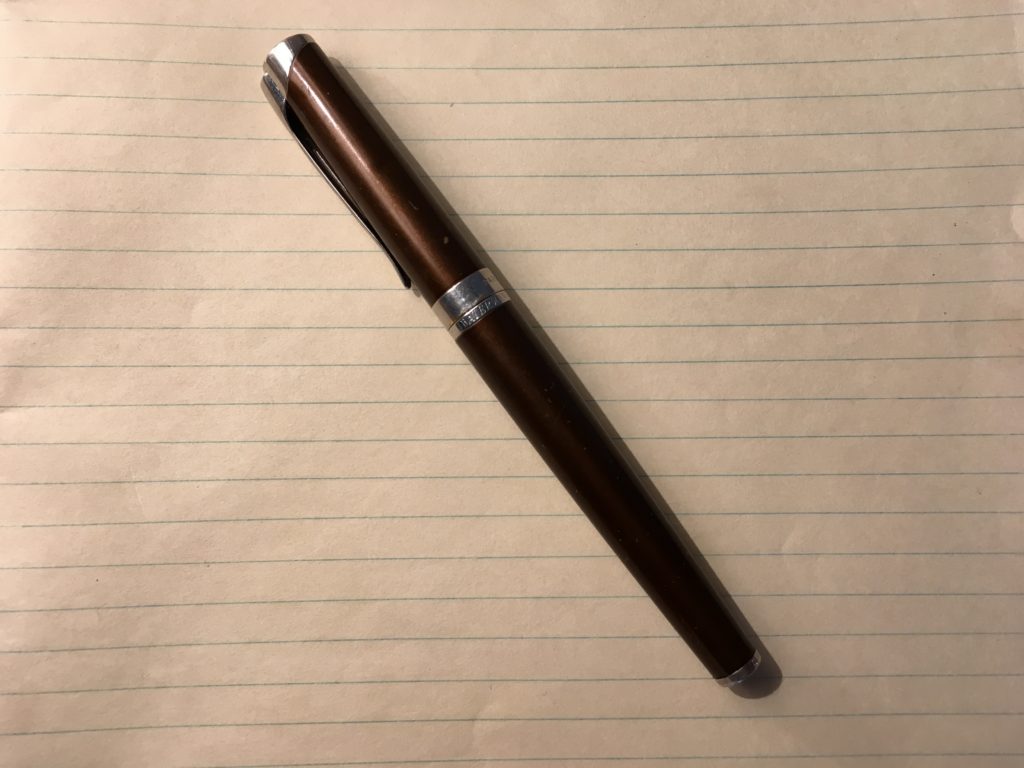

a pencil and an old envelope to write down what I found.

I was soon in a realm quite unknown to me. Lost in English just meant lost to me, but in Latin amissum seemed to some up how I felt about the loss, as did verloren in German. The Icelandic missti did this, too, but also evoked the atmosphere into which my personas and my homework had disappeared. The Hungarian elvesztett and Slovenian izgubli seemed to identify with whom they had gone and the Maltese mitlufa suggested the possibility that they had gone of their own free wills which was not encouraging. Why would they want to leave me? It was the Sesotho laleheloa ke that restored my confidence. It sounded like a rallying cry, a word that would pierce the mists and call those miscreants back.

When I caught the tram home that afternoon, I was fortified by the two humbugs adhering to my pocket lining and I felt better able to face the music. As I squared my shoulders for the upcoming ordeal my antennae began to unfurl. I thought I heard a familiar squeak.

Maud. Good old Maud.

Before I had time to open my arms to her the conductor came to punch my ticket. He narrowed his eyes at me. ‘Aren’t you the young scallywag that left its schoolbag on the tram this morning?’ He shook his head at me and waddled his way back to the driver’s cab.

It was all there. My homework, my atlas, my pencil case and my Uufgabeheftli – the exercise book that I wrote all my deadlines in. It was this that I picked up. I opened its back page, turned it upside down and made a list:

Verloren

Amissum

Missti

Elvestett

Izgubli

Mitlufa

Laleheloa Ke

I learnt the words off by heart, chanted them. Gradually my antennae unfurled fully, my personas returned and my grey world became colourful again.

To this day, when I lose my characters, I repeat the words, annunciating slowly as if I were listing railway stations or reading the shipping news, a steady hypnotic beat. They announce that my antennae are out, that I am ready to receive. The last word, though, is different. Laleheloa Ke is a call that has to be sung from the top of my burrow mound.

There will be no murmurs next week. Mole is on sabbatical