A long scenic detour to the Writers’ Cave and remembering how much I used to dislike walking.

Monthly Archives: January 2017

Mole Out Loud #520

Hobbling

Yesterday, had you been able to see under my pelt, you would have seen that my molechest was all puffed up – not with pride exactly, but with delight. I had reached the summit of Knocklofty after a break that I thought would last until Doomsday.

Great Uncle Mole was a great walker. He walked in blizzards and tempests, gales and scorchers. He would walk at least twice a day. On his early walks, three, four hours sometimes, he required solitude. But in the afternoons he required company and when I was staying with him I was the company he required, though often Uncle Ratty came too.

There was a time when I balked at these walks, his stride was so much longer than mine, his puff so much greater. But as I grew my wheezles lessened and I found I could ease from a canter into to a trot and still keep up. After a while I began to realise that not only had I reached his pace but that Great Uncle Mole was beginning to slow down.

When was it? I can’t remember the year but it was late one autumn, the snippid dankness of rotting leaves assailed our snouts, the acrid bite of woodsmoke caught the backs of our throats. I had arrived the evening before and it was our first venture out. We donned duffle coats and gumboots as we always did that time of the year, and grabbed umbrellas from the stand, just in case.

I didn’t really notice at first, we had been climbing a small hill using our brollies as Alpenstocks, had stopped briefly at the top to watch the 4.16 from Paddington wind its way through the valley, and were now making our way along the crest. It was our habit, or at least a habit that I had copied from Great Uncle Mole, to carry our closed umbrellas against our shoulders as if we were soldiers with rifles. But Great Uncle Mole was continuing to use it as a stock. At first I thought he was being absent minded, not that I’d ever known his mind to be absent; he was the most mind-present mole I have ever known. Then I realised he was leaning on the umbrella. In fact he had a distinct hobble. And now I came to think of it, he had not been out in the morning, or hardly anyway, only down to the newsagent to pick up a copy of Meccano Magazine, because he thought ‘d be interested in an article he’d seen about tunnelling under the Thames for the East Anglia Railway.

There were days when his gammy leg just seemed a nuisance to him, but on others it seemed to me that if I had been able to light up his body according to where his focus lay, I would have seen that it had been sucked from his head to feed the beast that his gammy hindleg had become. He was terse on those days, angry with himself (and anyone around), frustrated at not being able to walk further, get his mind back where it belonged and not trapped where it had no business to be.

My pleasure in walking has increased with age just as my physical capacity has declined. I hobble and limp; if it is not my hip then it is my ankle, and when it’s both I feel incredibly old, older than I ever imagined Great Uncle Mole to be. I feel as if I have grown into the kind of old that I drew when I was a nipper; old moles were bent double, wore spectacles and leant on canes. I felt defeated.

But then after months and months there is a glimmer that this might not be a forever and forever; it may be some of the time, even most of the time, but not all of it, not yet.

Gaining the top of Knocklofty I began to feel a sense of flow. The hours of walking loosened my thoughts, mulched the layers of debris that had sunk into my inner being, and allowed my imagination to wander free.

When I next went to stay with Great Uncle Mole his hobble was greater but his mood had lifted. He had gathered a collection of walking sticks, took pleasure in selecting the one he would take out on any particular day. He didn’t walk as far but had earmarked fallen logs, styes, low walls and large rocks where he could sit and ponder. I was no longer expected or even invited to accompany him. It was Uncle Ratty who told me about the resting places.

No nipper could resist the temptation of treating the information as if it were a treasure hunt. And it was much more of a treasure hunt than I had expected, because in each spot there was a cache containing apples or nuts or a puzzles, and in one even a small book covered in oilskin. I thought they were for me and stuffed them into the pockets of my duffle coat. But then I discovered one with a note from Uncle Ratty that was so clearly intended for Great Uncle Mole that I was mortified at having trespassed and I retraced my steps and put everything back.

I wish now I could talk to Great Uncle Mole about how he managed to get his mind away from his leg and back into its rightful place, how he found a way of being himself notwithstanding the shrinking of his horizons.

Mole Out Loud #519

Mole Out Loud #518

Mole Out Loud #517

Mole Out Loud #516

Mole Out Loud #515

Mole Out Loud #514

Mole Out Loud #513

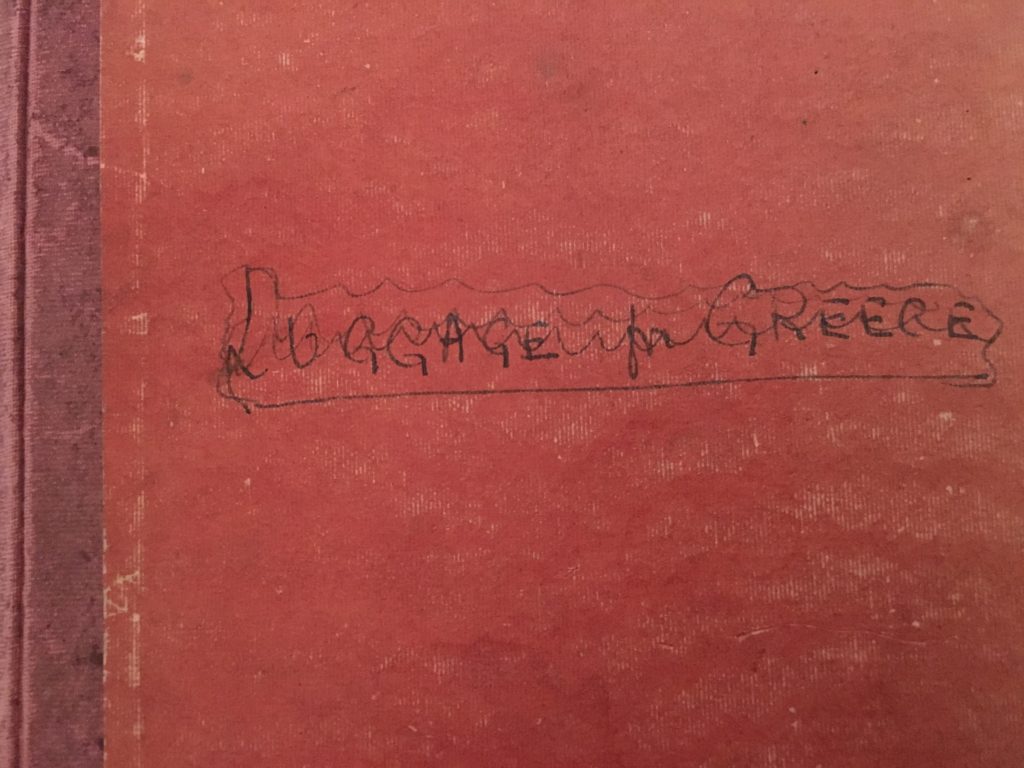

Remembering an exquisite place and terrible writer’s block.