A wild and woolly day, a midday treat, and pleasure in writing murmurs.

Monthly Archives: September 2016

Mole Out Loud #447

Mole Out Loud #446

Mole Out Loud #445

Mole Out Loud #444

Kerning

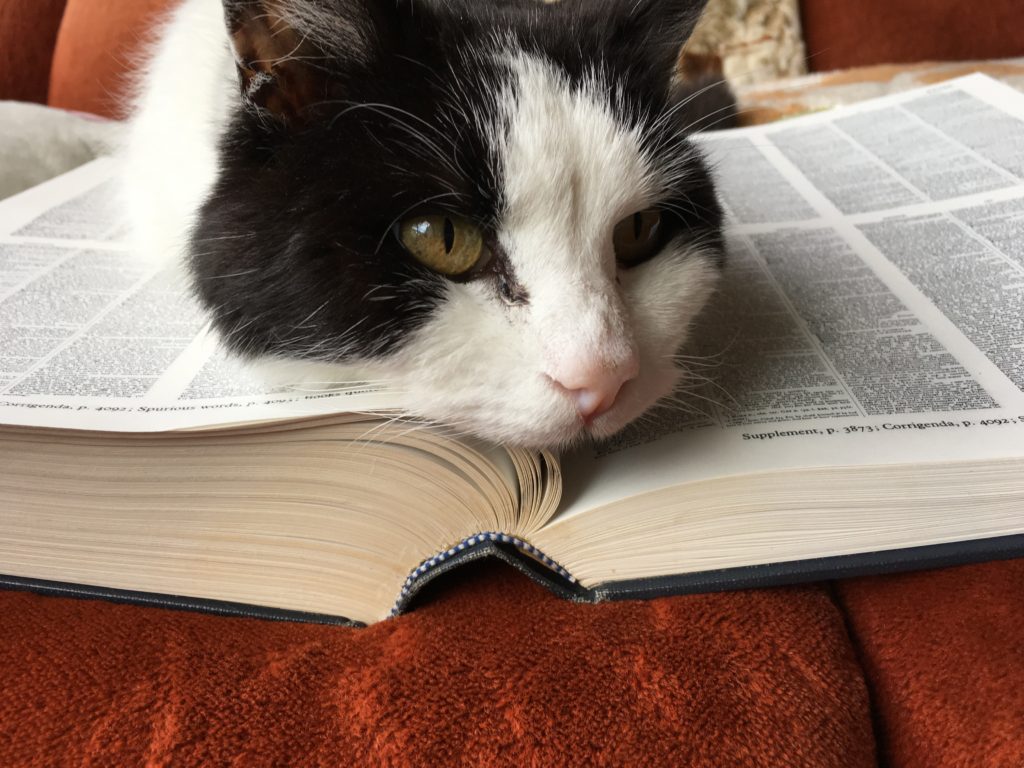

The other day I was looking again at the lyrics of the Marseillaise the Chelsea Rat had printed for me after the great storm; well not the bloodthirsty lyrics so much as the font. It is lightly seriffed and in one or two cases, particularly at the beginning of the third and fourth verse, the tongue of the Q has such a long flourish it underscores the u next to it. I remembered then the old typesetter sitting in Great Uncle Mole’s chair, placing slugs into his composing stick as he gathered his fragmented self back into his skin, and how sometimes there would be a slug that held a letter that didn’t fit on its shank. It reminded me of the way one’s paw sometimes flings off a sheet on a hot night and sticks itself out over the side of the bed so that the air can circulate around it.

Recently my burrow underwent a transformation. No walls were ripped down, nor chambers added, no paint was applied, nor was much done in the way of tidying up. A room was prepared; but that in itself, although symptomatic, was not the transformation.

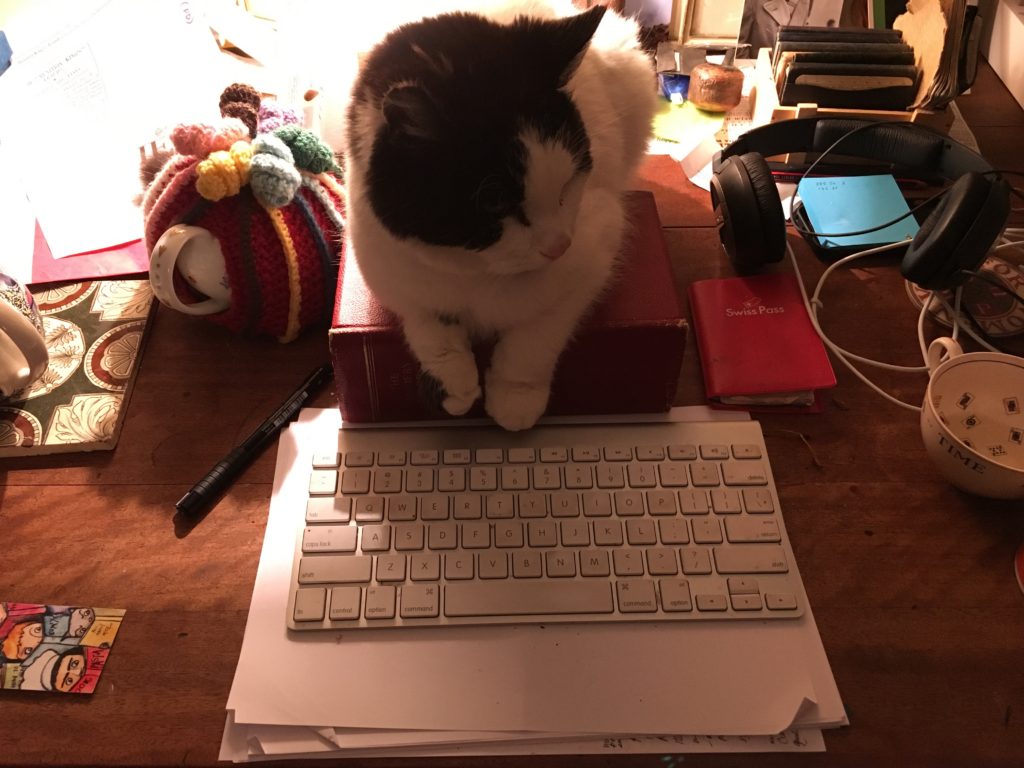

I have become used to the boundaries created by the walls of my burrow. They have become so immutable that I rarely have to negotiate them. I am free to potter about, write wherever the mood takes me, graze from time to time, puff myself up, shrink myself down, snooze or sing. I am surrounded by a kind of – I was going to say white-space, but that most emphatically is not the kind of space within the walls of my burrow. I am surrounded by the flotsam and jetsam of a lifetime’s accumulation; not just my lifetime either because of course in my cellar I have the bits and pieces Great Uncle Mole hoarded or inherited or somehow gathered up from his forebears; and Uncle Ratty’s too, and those of my Mama and Papa.

Notwithstanding the almost archeological hoard my burrow contains, it is not often it is inhabited by anyone else. But last week a chum came to stay. It was the first time anyone had stayed in my burrow with me in six years.

This chum and I have lived in each other’s burrows before, and there are bits and pieces from my chum’s life here as well, a dresser, a chair, notes, plants in the garden, memories. At one level – a good solid earthy sort of level, we are as comfortable as old gumboots but we are also as different as can be. My chum is a sociable creature, always on the move, always on the search for new adventures. And I, as you know, am drawn towards silence, nestling and being unplugged.

It is not that I am not free to do potter, write, puff and whatnot, but for the first couple of days my chum was here I was hyperconscious of my actions, and hyperconscious of the time I spent not interacting.

What, you might ask, has this to do with slugs with letters that won’t fit on their shanks. Well, there is a name for the bit of letter that hung, paw-like over the edge. It is a kern. And the function of these slugs is to allow for letters to adjust themselves differently depending on what their neighbouring letters might require; the amount of space is subjective, more to do with perception than measurement. The first of the two small ffs in differently bows its head over the second. The second creates a canopy over the e that follows. In subjectively the j almost spoons the b to its left.

Some letters kern more than others. O for instance, unless italic, does not kern at all; its midriff buffers it from contact with any letters that do not have an overhang; it relies on others to make any adjustments.

It strikes me that in the household of Great Uncle Mole and Uncle Ratty, that Great Uncle Mole was an o and Uncle Ratty more of an f or a Q. Without Uncle Ratty’s adept kerning they would never have remained such good chums.

I recognise within myself a certain amount of Great Uncle Molish oness, which makes it easier to lead a solitary life, but the opposite must be true for the kerning kind. I imagine a sense of unrightness if they do not have a neighbouring letter or being to kern with. And then there are those who have kerned all their lives with one particular being and, in typographic terms have become ligatures like the German ß (eszett) which is a double s, or æ (ash). How then, from such an entwined state, can the loss of one part be endured?

I suspect once an o always an o, but now that my chum has departed I am missing the patter of her paws.